Summer of 1862 Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest reached Helena, Arkansas, on July 12, after a grueling and toilsome march. Though Curtis wanted to secure the state for the Union, he was forced to move away from the capital towards the Mississippi River in order to procure a consistent line of communication and supply. The move to Helena secured the town for the remainder of the war, but ended Curtis’s summer offensive to secure Arkansas and Missouri. And though he failed to keep Arkansas, he did deliver Missouri and ensured a strong Union presence in Arkansas.

The result was a bit of a lull for the Army of the Southwest as it sought to fortify Helena and recuperate. But not all of the army stayed in Helena. Several regiments were ordered south to a dilapidated landing on the Mississippi River called Old Town, a place “so old it has disappeared,” declared one soldier. The location, described as a mosquito infested and “fever-breeding swamp,” where “the men…sickened and died by the score.” But more importantly, a place with no apparent strategic value by occupying it. However, not long into their stay the reason became apparent, as one soldier bluntly described, “[we are] stealing and smuggling cotton.”

The men involved in these “cotton expeditions” were made up principally from the 33rd Illinois and 11th Wisconsin; soldiers who barely had time to recover from their experiences during the past several months’ campaign.

During the summer’s campaign the men had experienced guerrilla tactics that resulted in violence many had never seen before, “they tied to a tree & shot one of the Wis Boys …[he] was filled with shot.” Henry Twining of the 11th Wisconsin noted the same event in his diary, “two of our orderly sergeants were captured by the Rebels.” The Bushwhackers had “lash[ed] them to a tree” and executed them with a “savage barbarity.” Both bodies were riddled with bullets, one with 13 and the other sixteen. In another incident, a soldier from the 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry was captured and dragged into the woods, where bushwhackers reportedly “cut off his nose, gashed his check, and then cut his throat in three places.” Miraculously, he managed to get away and survived to tell his story. Colonel Albert Brackett of the 9th Illinois Cavalry reported that “an example must be made in some way here, or our soldiers and expressmen will be assassinated on every occasion.” By day local citizens, reported Brackett, acted like “good Union men” and by night took up arms as guerrillas.

And it was not just the local men who were to be feared. Women were often described as “she devils” who were feared by the men and one living near Helena was described as a “bushwhacker” who carried a Bowie hunting knife, which she used to reportedly kill “seven men.” One soldier even commented that he “never thought… [before] like shooting a women” until he arrived in Arkansas in 1862.

From the start these cotton expeditions attracted the attention of bushwhackers and guerrillas who organized ambushes, while Confederate Cavalry and Infantry (such as the 28th Mississippi Cavalry regiment) engaged in hit-and-run tactics that sometimes involved small canons. But usually it was small bands of guerrillas who targeted the slow moving boats that ferried the soldiers down river to the large plantations that were their targets. Shooting from the shore and then fleeing deep into the woods made them almost impossible to catch. At times transports took canon fire, men were killed and or mangled, and eventually Union gunboats and rams were utilized as the attacks increased.

A soldier with the 11th Wisconsin wrote home from Old Town, “[they] went back to the Old Testament doctrine” of warfare. He referred to the women in Arkansas as “she Devils” and that every one of them, including children, should be removed and “hungry flames set upon” their homes. This declaration occurred after the brutal lynching and hanging of several Union soldiers by Bushwhackers. He finished his tirade, stating bluntly, “hereafter, temper the warfare with more justice, and less mercy. We must crush these rebels, though we have to descend to their arena of fighting to accomplish it.”

When on ground in search of cotton, the enemy often appeared in ambush, sometimes in force, one such incident “a band of one hundred and fifty bushwhackers” attacked and a savage fight commenced. “We went out in the dark evening hours,” wrote a survivor, to dig graves in “Arkansas soil,” and as they did they swore a “renewed pledge” to do justice to their enemy.

As each side struck back at the other, an Arkansas native noted that “the spirit of resistance is stronger than ever, but it is, I fear, stimulated by revenge.” Revenge would motive both sides to continue savagely attacking the other. The enemy were often given no quarter, as it was reported that one bathing Federal soldier was found dead in the river “shot and beaten to death with clubs,” leading General Curtis to declare the region occupied by a “set of assassins.” The after affects of such violence led both sides in the conflict to come close to “mass executions” of prisoners who they deemed to be bushwhackers and common criminals.

Tempers flared and soldiers where sometimes quick to respond. July and August had been extremely hot causing eight men of the 33rd Illinois to be “prostrated by the heat,” while out on a cotton gathering mission. The heat, exhaustion, paranoia, and angst felt by most men could and would lead to atrocities. The enemy made it known that there mission was to “attack…day and night,” to kill “scouts and pickets” and “kill his pilots and his troops on transports.”

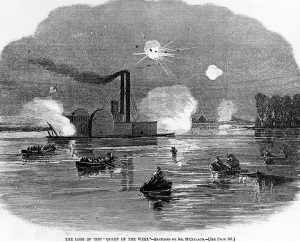

On the morning of September 14th, 1862, after enduring weeks of “cotton expeditions,” having seen comrades cut down by guerrillas and bushwhackers, six companies of the 33rd Illinois boarded two transports, the Iatan and Athambra, escorted by the ram Queen of the West. They road “quietly and pleasantly” downstream for most of the morning and enjoyed the fresh breeze blowing off the river. Across from the mouth of the Arkansas River rested the small town of Prentiss, Bolivar County, Mississippi. As the convoy swung around to the Mississippi side of the river, the quiet was suddenly broken by the crackling of gunfire as a hundred or more guerrillas opened fire in an ambush.

On the morning of September 14th, 1862, after enduring weeks of “cotton expeditions,” having seen comrades cut down by guerrillas and bushwhackers, six companies of the 33rd Illinois boarded two transports, the Iatan and Athambra, escorted by the ram Queen of the West. They road “quietly and pleasantly” downstream for most of the morning and enjoyed the fresh breeze blowing off the river. Across from the mouth of the Arkansas River rested the small town of Prentiss, Bolivar County, Mississippi. As the convoy swung around to the Mississippi side of the river, the quiet was suddenly broken by the crackling of gunfire as a hundred or more guerrillas opened fire in an ambush.

In the 1860s the fertile land of Bolivar County was sparsely populated with a few plantations and small farms. Resident J.C. Burrus described the region as consisting of “primeval forests” where in the warmth of a hot and humid summer, “they were a wall of living green, towering up into the heavens.”

“In the first days of our county the planters protected their lands from overflow [from the bayous and streams],” Burrus described, “as far as possible, by private levees thrown up with plows, spades, and shovels.” Slaves helped planters cultivate the land and created networks of small levees along the swamped river front.

The region was thick with trees and underbrush, perfect for Bushwhackers, Guerrillas, and Partisans to wage a war of attrition against the Yankee invader.

From 1855 to 1860 the region experienced an eruption of cotton farming as plantations sprouted up. Settlers converged on the area, “many of them slaveholders, and large and numerous tracts of land were cleared and cultivated.” The slaves performed the backbreaking work of road clearing and paving. Soon small communities and townships developed. One of these small towns was Prentiss, located not far from the Mississippi River.

After crossing the large river, the Iatan stopped and took on two slaves who caught their attention along the shore. Charles Wilcox was on the Alhambra which passed the Iatan and continued downstream.

The initial blast from rebel gunfire hit the Iatan, which was now a distance behind the Alhambra and the gunboat escort. Two unsuspecting soldiers were killed along with the two slaves. Many others were wounded. Immediately the gunboat turned about and opened fire, shelling the woods. For about 30 minutes the woods and brush along the river were uplifted by canon fire. With comrades killed and others wounded, the ships anchored and two companies, including Charles Wilcox, gathered up “turpentine and pine knots” and heading towards town.

The expedition was led by Lieu. Col. Charles E. Lippincott who filed no report concerning the events that were to follow. Lippincott lead the men to within a short distance of town and sent a soldier with a flag of truce and specific instructions that the women and children had 30 minutes to leave their dwellings. Skirmishers were sent out in case the rebels decided to come back. After time was up Lippincott led his men into town.

“We burnt every thing, a single thing not being allowed to be pillaged,” he wrote. They did not ransack any houses and they did not confiscate any supplies, they simply and methodically put to flames every single dwelling. “I saw a great many things which we as soldiers are actually in need of,” said Charles Wilcox. But the orders were strict: everything was to be destroyed, nothing taken. “Pianos, guitars, melodeons, superior household furniture of every kind” were engulfed in the slams. A store, “full of goods,” Charles observed, was consumed. The town consisted of about thirty buildings including a courthouse, “with all the county papers,” a jail, tavern, and a couple dozen homes were all destroyed. Lippincott later reported that “about $100,000” in property was destroyed that afternoon.

No one was killed, no pillaging or raping, and to the men of the 33rd Illinois – as well as Lieu. Col. Lippincott – they were simply delivering a “just retribution.” For them it was an act of justice.

“This is the destruction the rebels brought upon themselves by their dastardly skulking in the brush on the bank of the river and firing into us,” declared Charles Wilcox in his diary. “Our Liet. Colonel… believes in just retribution.” They stood and watched the flames consume the town, not leaving until they were sure it would all be in ruins by dark. They returned to the boats where they could see the flames atop trees and smoke drifting away on the horizon.

The attack was reported by a local newspaper a short time later:

“Another Town Destroyed.—We learn from a friend who resides at Napoleon, that he witnessed the burning of the town of Prentiss, on the Mississippi, opposite Napoleon, one day last week. It appears that three federal soldiers were killed in the vicinity, and the yankees came up with gunboats, shelled the town for hours, but failed to destroy it. They then went ashore with torches and fired it. The place is now a complete ruin. The behaviour of the women is said to have been remarkably courageous. While the shells were flying they remained in the town and when the ruffians landed with the torches, the women stood by, reviling them for their cowardice.”

These men did not charge into town, cut down innocent women and children, murder, rape and pillage. Why? Because they were not morally able to do so. They were products of their culture. They were waging a war on a foe they knew and for the most part respected. It never occurred to Lippincott or his men, even though they were enraged, to march into town unannounced and wage war against the civilians.

Some historians define “total war” as the complete disregard between combatant and non-combatant, while others as the “disregard of restraints imposed by custom, law, and morality on the prosecution of the war.”

It appears that Lippincott and the Federals made no distinction between secesh or Union when they burnt the town. But were the people of Prentiss guilty of anything? Did they deserve to have their town destroyed as a military target?

Mr. Burrus, who was a young boy at the time near Prentiss, recalled that, “between 1862 and the close of the war a number of pilots and other Federals were killed on the boats of the Mississippi River by sharpshooters (snipers).” Preeminent among them was “Judge McGuire,” who Burrus noted was “a fine rifle shot, and also a cool, fearless man.” Apparently this judge possessed a powerful and accurate rifle. Within two years Burrus himself still a young boy took up arms and fought. There could be little doubt that the husbands, sons and even grandfathers of the town were probably involved in some fashion.

Brig. Gen. James R. Slack of 47th Regiment Indiana Volunteers, stationed in Helena, wrote that “Prentiss is, or was a terrible traitor hole, a rendezvous for the worst kind of scoundrels… committed the highest crimes known to the law.” And it was only the fear of punishment that “keeps them anywhere in the bounds of civilization.”

If interested contact the author for works cited.

Pingback:Best of the Blogs (6-9-2017) | Civil War Chat